Photo by Jason Henry

Wayne Thiebaud at his studio in Sacramento.

Having His Cake and Eating It, Too

By Jessica Zack

October 12, 202

Wayne Thiebaud shook up the art world in 1962 with paintings that were joyous, confectionary, and uniquely Californian. Since then, he’s worked steadily, producing sought-after pieces noted for their originality and impact on American art. On the eve of his 100th birthday, the artist says he’s “trying to learn to paint” and put a smile on people’s faces.

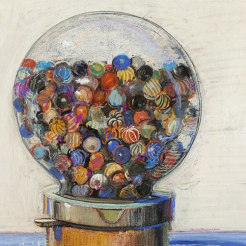

In the summer of 1961, Wayne Thiebaud, at age 40 and just one year into his position as an assistant professor of art at UC Davis, loaded up his car with his new paintings, unpretentious depictions of edible Americana—hot dogs, ice cream cones, cakes, pies, and gumball machines—and drove cross-country with fellow Sacramento artist and former student Mel Ramos to look for a New York dealer.

A former commercial illustrator and cartoonist, Thiebaud had an eye for the irresistibility of goods on display and a nose-to-the-glass nostalgia for the sweets and cafeteria staples of his youth spent in Long Beach and hardscrabble southern Utah.

He was a self-taught artist with voracious art-historical curiosity and reverence for the old masters (particularly, still-life virtuosos Chardin, Morandi, and de Chirico), and he had already shown his work on the West Coast in numerous exhibitions, including his first solo museum show a decade earlier at Sacramento’s E.B. Crocker Art Gallery (Influences on a Young Painter—Wayne Thiebaud). But he was still searching for his own answer to the endless conundrum of what exactly to do with the brush in his hand, standing before a two-dimensional blank canvas.

Before landing on his breakout, signature style of painting everyday consumer goods and bakeshop confections—candy apples with tactile stick and shine; layer cakes on spindly plates, in heavy impasto mimicking frosting—Thiebaud was largely unnoticed by an art establishment besotted with the postwar drips and color fields of the abstract expressionists. Emotion and (masculine) myth held sway with the East Coast critics and blue-chip galleries, not the perfect geometry of a neatly sliced, ready-to-serve cheese round.

In Manhattan, Thiebaud devoted a day to walking up Madison Avenue from Midtown, calling on the district’s many art galleries. He was summarily turned down at each stop and eventually found himself heading west, toward Central Park.

Art dealer Allan Stone found the dejected California painter resting his legs and bruised ego, with a fat roll of canvases under his arm, outside Stone’s new townhouse gallery space on 82nd Street.

“You wouldn’t be interested in these,” Thiebaud said. “Nobody else is.”

He couldn’t have been more wrong.

Stone, having coaxed Thiebaud to let him take a look, found he was puzzled and transfixed by what he saw. (“My first reaction was, This guy must be nuts,” Stone once told CBS.) He offered Thiebaud a solo show the following spring.

That 1962 exhibition was an immediate, phenomenal success and indelibly marked Thiebaud’s entrance into the national conversation about where American art was headed. Every painting sold, to prominent private collectors as well as the permanent collections of the Guggenheim Museum and the Museum of Modern Art. National magazines wanted to interview the modest Northern California art instructor with the industrious, Depression-era work ethic and deadpan sense of humor.

“Wayne’s work was so suave by comparison with other pop artists of the time, whether it’s early Warhol or Lichtenstein,” says Kenneth Baker, the longtime San Francisco Chronicle art critic and coauthor of a comprehensive 2015 monograph on Thiebaud’s oeuvre. “His paintings had a confectionary, delectable quality that people found inherently appealing on sight. They were clearly disciplined, yet indulgent toward the spectator’s pleasure. The appetitive attraction that art can exert on its viewers had never been, in my recollection, so plainly declared as it was in Wayne’s work of that period.”

When pop art exploded later that same year, and Thiebaud’s color-blocked lollipops and pillowy meringues were displayed alongside Lichtenstein’s brash comics and Warhol’s soup cans in the first-ever pop art group show (the Pasadena Art Museum’s New Painting of Common Objects), Thiebaud’s fame took on even greater dimensions, even though his connection to pop has always seemed to him like a misalignment.

Thiebaud wasn’t aiming for social commentary with his depictions of mass-produced abundance. He never intended to satirize postwar consumer lust.

“I hope not,” says Thiebaud, now age 99, on a June 2020 afternoon, during the first of several wide-ranging conversations we had about his life and his art. “I’m essentially very positive, and I like to feel celebratory about the work. Most of it should feel joyous.”

He’s always been a California optimist at heart, and he doesn’t believe, as some critics do, that serious art is debased in any way by humor or by aiming most of all to delight.

“I think I was kind of spoiled as a boy,” Thiebaud says. “I had wonderful parents who spoiled me. If I did things now that were other than joyous, let’s say that were dark and moody, I would be having to fake it.”

“Most of all,” he adds, “I like to see people smiling when they look at my paintings.”

It’s frankly impossible for me not to smile during a visit to Thiebaud’s midtown Sacramento studio. It’s housed in a nondescript, gray one-story building across the parking lot from a discount grocery store. Canvases by one of the most respected and beloved painters alive lean against the walls on both sides of the long space, and it’s breathtaking being confronted in person with most of his major themes—his food paintings; his iconic, vertiginous San Francisco cityscapes; his Sacramento River delta landscapes, beachscapes, and quasi-abstract mountain studies—all in such casual arrangement.

Toward the back of the room are a number of paintings of clowns, the most recent subject to capture Thiebaud’s attention. He says these jesters hold some indescribable mystery for him; he can’t decide whether they’re menacing, slapstick, or something in between. He recently painted one in full makeup behind the bars of a jail cell and another with his hair on fire.

Thiebaud has spent the past six years on the clowns, and he says that he usually spends at least a decade working through a specific subject matter. “You don’t realize it at the time, but it happens.”

For instance, when he bought a house in San Francisco’s steep Potrero Hill neighborhood in 1972, he started a consuming series of cityscapes—now iconic and instantly recognizable as Thiebauds on ubiquitous posters and postcards—distinguished by their extreme angles and exaggerated chaos.

“I was fascinated by the way in which, at intersections, four different roads came in at different angles,” he says. “There were these cascading roads with parallel skyscrapers and buildings, which made it look almost like big, square rocks on the side of a waterfall, with cascading automobiles, and raised the question of whether they would be able to really sustain their position on the road. That was a wonderful challenge, to try and see if I could express that. Looking at them, you should feel a sense of disequilibrium.”

When Thiebaud emerges from the back office, which is lined to the ceiling with art books and where he likes to read each day, he moves briskly through the gallery and greets me. He’s charming and inviting. He squats down low in his Lacoste slip-ons to look closely at his work. A palette with dabs of fresh paint and a wet brush rest on a wooden bench. Names of artists and authors tumble forth in conversation. His face is remarkably unlined despite his decades on the tennis court. Perhaps the only sign of Thiebaud’s advanced age is that his low-pitched voice grows hoarse after about 20 minutes of talking.

Thiebaud is in robust health, his droll sense of humor and upbeat spirit intact. A life of routine and rigor has clearly served him well. He’s as self-deprecating as ever, and, notably for someone turning 100 on November 15, he still adheres to a daily schedule that has altered very little over the course of seven decades.

He’s up early every day, motivated to head into the studio each morning by what he modestly calls “this almost neurotic fixation of trying to learn to paint.” “It’s rare that I’m not in the studio,” he says. “That is the program that seems to have been my lot.”

After breaking for lunch, until the COVID-19 pandemic hit, Thiebaud would play doubles several times a week with old friends at the Sutter Lawn Tennis Club. “I still play, but it’s a kind of insult to the game at this point,” he says.

“And then in the afternoon, it’s back to [painting].”

Thiebaud has lived in the same modest house in Sacramento’s Land Park neighborhood since 1971. His wife of 56 years, Betty Jean, died in 2015. Their son Paul, an art dealer who represented his father and others, through galleries in San Francisco, New York, and Sacramento, died in 2010. Thiebaud has three surviving children and six grandchildren.

“My world hasn’t changed much,” he says of the current lockdown. “I’m usually in the studio most of the time anyway. I do miss going out to restaurants, seeing my friends.”

Thiebaud is open-minded about the possibility that work itself—his ritualistic, daily discipline of “visual inquiry,” a lifelong practice of training himself to see more attentively, to distill reality into satisfying compositions—may be life-sustaining.

There’s a fascinating paradox at the heart of Thiebaud’s art practice, which becomes clearer the more we talk: He works with a compulsive attention to detail and has a perfectionist’s eye for finding flaws, quick to needle himself about where he’s fallen short of his ideals, and yet he avows an unwavering love for the process of painting itself, despite its inherent frustrations and his frequent discontent.

I ask him if he ever looks at his work in the studio and feels satisfied.

“It’s very, very rare,” he says.

Thiebaud’s longtime friend Gene Cooper, a Laguna Beach artist and art historian, sees Thiebaud’s diligence as a product of his Mormon upbringing (he left the church as a teenager when expected to go on his mission) and central to understanding his drive to revisit and rework his earlier canvases.

“Wayne developed a work ethic that he would carry into his adult life as well as his art and teaching careers,” says Cooper. “It would never disappear. It was a moral issue. In a way, work is his subject matter, an ongoing process without an end. He does not wait for inspiration to guide him. It is work that directs his journey.”

Thiebaud is famously allergic to philosophizing about his own work, but he does admit that it’s reasonable to read irony or a subtle, winking presence in many of his paintings, although it’s always in the back seat, with material, formal concerns (“making a composition that works”)—and, of course, nostalgia—up front.

“It’s a wonderful combination of memory, imagination, and direct observation,” he says. “A lot has to do with yearning.”

“Primarily,” he continues, “what I’m interested in and always have been is this wonderful, personally involving search to find out all I can about painting, to be willing to take risks and try things that don’t seem to be logical, and find out how my feelings and experiences as a boy growing up in America can be reflected in a painting.”

Thiebaud was born in Mesa, Arizona, and spent most of his childhood in Long Beach. He has fond memories of being a teenager on the coast, working as a lifeguard, hawking newspapers on the beach, and selling stacked ice cream cones and hot dogs at a popular café.

He also recalls how formative the two strapped years were that his family spent in Utah in the 1930s after his father, a Mormon bishop, lost his mechanic’s job and tried his hand, unsuccessfully, at ranching.

Those boyhood memories of the land and the stark light, the feeling of being dwarfed by the vast western terrain, have deeply influenced Thiebaud’s approach to landscape. People never appear in his semiabstract mountainscapes, yet a hint of human scale—a tree atop a bluff, or a lone cabin—draws the viewer into the frame. “I look at the paintings and try to actually imagine how I would walk along a little top edge, or how would I feel diminished by being underneath a huge outcropping,” Thiebaud says.

Since the 1990s, he’s produced dozens of paintings of the Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta, a source of ongoing inspiration. In his distinctly fauvist, playful colors, golden furrows are bisected by gem-tone rivers snaking through pastel-hued fields dotted with orchards.

When you look closely, you see that he combines several perspectives into one frame. The delta paintings appear to be bird’s-eye views, “but I’ve never gotten up over about 25 feet to look, so those [vistas] are all imagined,” Thiebaud says.

He has been drawn again and again to the striking tonal shifts of the delta’s seasonal changes, something that escapes most visitors to this lesser-

known area of Northern California.

“There are a thousand miles of waterways, largely unknown to very many people, and these winding rivers and lagoons and islands form an amazing array of patterns,” says Thiebaud. “In the winter, the landscape would be very dark and dreary and foggy and almost black when the fields were vacant; then the spring would have these wonderful, fresh, bright greens and almost lively yellows coming to life. Then in the summer, where things were more golden and palomino-colored and brighter, and stronger dark shadows were cast. What I’m pointing out is that what I tried to do was not to make a specific area or specific place pictorially, but to use those various seasonal and color changes to make essentially a kind of abstract representational combination, trying to combine as many of the seasons and colors as seemed really interesting and compelling.”

To celebrate Thiebaud’s 100th birthday, the Crocker Art Museum, which has hosted a Thiebaud show every decade since 1951, has planned a massive retrospective of his artwork in all media, including numerous works from the artist’s collection that have never been publicly displayed.

Wayne Thiebaud 100: Paintings, Prints, and Drawings is currently scheduled to be on view from October 11, 2020, through January 3, 2021, and then will travel to four other American museums: the Toledo Museum of Art, in Ohio; the Dixon Gallery and Gardens in Memphis; the McNay Art Museum in San Antonio; and the Brandywine River Museum of Art in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania.

Thiebaud, who has visited the Crocker regularly and donated to the museum generously since making Sacramento his home in the 1950s, “had a big hand” in what was included in the centennial exhibition, says Scott Shields, the Crocker’s associate director and chief curator. Iconic Thiebauds are there in abundance, but so are “some things you might look at and not even realize they’re his.”

“One of the things I most admire about Wayne is that he never just stuck with one thing,” says Shields. “A lot of artists find success, and they just do it the same way for the rest of their career, especially in the contemporary realm, but he was really cognizant of not wanting to get stuck. He’s never sat still and rested on his laurels.”

Thiebaud is voluble when it comes to art history or his love of teaching. (He officially retired from UC Davis at age 70, continued to teach as an emeritus professor until 2009, and still occasionally sees students privately.) “Wayne has always felt, even when he was starting out, that he was a teacher who painted, as opposed to a painter who taught,” says Laguna Beach artist Fred Hope. For the past six years, Hope, who is 68, has driven north to Sacramento “with a carload of new work” every six weeks (the pandemic has curtailed his visits) for an afternoon of private instruction at Thiebaud’s studio.

The two met at an exhibit in 2011 after Thiebaud saw Hope’s work and told Gene Cooper that it was “well painted, but rather ordinary” and that Hope should push himself to make it extraordinary by making it more personal. Cooper relayed the comments. “It was exactly the right thing for me to hear at that time,” says Hope.

“He doesn’t talk down to students, and there’s a peer-to-peer feeling that makes you feel you could really achieve something if you work hard,” Hope says of Thiebaud. “He climbs right down off any pedestal. He doesn’t really like to talk about himself, but he loves to talk about examples, about what he learned from Richard Diebenkorn, or from [Willem] de Kooning. The thing he gets across is how much he loves doing what he does. It’s impossible not to be affected and stimulated by that.”

Thiebaud is also a master at deflecting a compliment. He shrugs when the subject of prices for his work comes up.

In July, one of his monumental paintings from 1962, Four Pinball Machines, measuring 68.4 by 72 inches, was sold at Christie’s One auction for $20.1 million, more than doubling his previous record, from 2019, when Encased Cakes (2010–11) went for $8.46 million.

Looking back over an exceptionally successful career spent doing exactly what he’s always wanted, Thiebaud agrees that by being associated early with pop art, he was “misunderstood into fame,” as Time magazine’s former art critic Robert Hughes once wrote.

“I don’t think I would have been known without being associated with pop art, even though I don’t even particularly admire the tradition,” he says.

Nearly 60 years after the seminal New York exhibition with Allan Stone, Thiebaud laughs when he recalls that formative period when he gave himself permission to stop aping the New York artists then in vogue and instead paint from memory the foodstuff and amusements of his youth.

Remembering his “first little pie painting,” Thiebaud says, “I thought to myself, That’s the end of me as a serious painter. Who the hell is ever going to be interested in these? But I just couldn’t leave it alone.”

Thiebaud credits one of his artist heroes, Dutch American abstract expressionist de Kooning, whom he befriended during a 1956–57 sabbatical in New York, with pushing him to develop a signature style and a subject matter all his own.

“De Kooning looked at my work and said, ‘This looks like the work of 100 people. You have to find something that you’re deeply in love with, or know a lot about, and take that as your subject matter. Don’t take the art world as your subject matter.’ So when I came back to Sacramento, I sat down and thought, I better think this thing out and start over,” Thiebaud recalls. “Because I was teaching, I gave myself an assignment to take basic shapes on a canvas—circles, ovals, squares, triangles. And then I thought, What will be my subject matter? I want something to sit on a plane and cast a shadow. And I thought, I’ve worked in restaurants. Maybe I’ll make those triangles into a pie.”

“Crazy as it seemed,” he says, “I declared then that I was going to grant myself the ultimate freedom, that I was going to paint what I really wanted to paint, any subject matter that for me seemed interesting, and I would paint any object, anytime, anywhere. And I’ve pretty much continued that. I never wanted to get repetitive. I wanted to change and explore as many different kinds of things as I could.”

At the start of one of my interviews, I ask Thiebaud what he worked on that morning.

“A self-portrait,” he says, the first one he’d attempted in several years. “That was a wake-up call to how much I need to do some more figures.” He tells me he also pulled out a “little beach picture” he’d done some years ago, to see if he could “make it look a little more interesting.”

Thiebaud’s long-standing habit of reworking older paintings, sometimes ones he hasn’t touched in decades, often leads to his work being labeled with multiple years, like Street and Shadow, an oil painting of a roller-coaster-steep San Francisco street in the Crocker show, dated “1982–83, and 1996.”

What compels him to return to a finished work after so much time?

“One just seems to sort of wink at you” from a corner of the studio, he says, “as if it’s saying, Why don’t you try this? What would happen if you did this?”

Thiebaud is above all a perpetual student. He describes days spent in the studio as akin to being a scientist in a lab. He’s at heart a tinkerer, a problem solver. “I think painting can somewhat parallel and duplicate scientific research, because painting really is a research,” he contends. “You have to try a lot of different things and be willing to have the painting begin to reveal itself. And it’s not like applied science, where there’s an answer or an end. Scientists, like painters, are always crediting accidents.

“Painting, in my opinion, is one of the most difficult things in the world to do. When you’ve seen the heroic accomplishments of Vermeer, Velázquez, Rembrandt, Picasso, and Matisse, and Middle Eastern, Japanese, Chinese painting…it’s overwhelming. You don’t want to ignoble that tradition.”

His voice trails off as if he’s silently questioning the whole lifelong endeavor.

“It’s actually almost ludicrous that anybody would do it,” he says.

I ask him if he believes in the Samuel Beckett dictum “Fail again, fail better.”

“Exactly. Yes. That’s very much a part of it,” he replies. “Serious painters spend an awfully long time looking at the work, speculating, hypothesizing, What would happen if I did this? So on and so forth. So in a way, you’re painting in your mind all the time.”

Thiebaud pauses. “I don’t think you can probably ever look long enough.”

Jessica Zack is a Bay Area journalist who writes about books, film, and visual culture. She wrote about Josie Iselin’s photographs of seaweed for Alta, Spring 2020.