Richard Diebenkorn

Figurative Works on Paper

March 19 – April 26, 2003

John Berggruen Gallery is pleased to present a major exhibition of early figurative works on paper by Richard Diebenkorn. This exhibition opens Wednesday, March 19th and will continue through Saturday, April 26th, 2003 at 228 Grant Avenue, San Francisco, CA.

Throughout his career Richard Diebenkorn was known for his early abstractions, (typified by his series of Berkeley paintings) his figurative paintings from the mid 1950's and 1960's, and his return in 1967 to abstraction in his Ocean Park paintings. This exhibition includes forty fully developed drawings and paintings on paper that illustrate the importance of the artist's figurative work and its relationship to his abstract works as well. A fully illustrated color catalogue will accompany the exhibition.

Born in Portland, Oregon in 1922, Richard Diebenkorn was educated at Stanford, UC Berkeley and California College of Arts and Crafts; Diebenkorn earned his M.A. at The University of New Mexico in 1952. He received the 1986 award from The American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters.

Richard Diebenkorn's work can be found in a number of important public and private collections, including the J. Paul Getty Trust, The Solomon Guggenheim Museum, The Smithsonian Institution, the Art Institute of Chicago, The Museum of Modern Art in New York, The Whitney Museum of American Art, The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Transparencies for reproduction available upon request.

An opening reception will be held on Wednesday, March 19th, from 5:30 to 7:30 p.m.

This exhibition of representational works on paper by Richard Diebenkorn introduces objects whose variety and quality is surprising even to those of us who thought we knew the oeuvre pretty well. For reasons more accidental than deliberate, many of Diebenkorn's drawings have remained out of circulation, possibly unseen even by the artist's closest dealers, curators and friends. We knew certain important works hadn't been fully brought to light, but not how extraordinary they were. Long before his death, and until recently, they were carefully stored in drawers, not gotten around to, perhaps not pulled out by the artist while he was working with a museum scholar simply because others were more to hand. The fortunate occasion of these works' excavation is an event to be taken seriously indeed.

In this show we are faced with an opportunity to reassess this artist's fundamental balance of priorities. In all of the quite voluminous writing on Richard Diebenkorn's art, several themes were developed early, and have been revisited. Perhaps the most fascinating and puzzling aspect of his prodigious evolution is his trajectory from a youthful yet markedly mature abstract style (a body of work nearly unequalled in the youthful period of any of his peers); into a prolonged era during which the artist drew and painted figures, still lifes and landscapes; and then into the great final cycles of abstract paintings and drawings known as Ocean Park works, and the Clubs and Spades. Each of his critics and scholars has pondered these shifts, and the strange repleteness of each phase.

The second remarkable fact of Diebenkorn's artistic approach is his lifelong project of mastering various media, and—perhaps even more difficult—his ability to work with equal proficiency in dramatically different scales. During virtually every stage of his explorations, he alternated between working on paper and on canvas, one medium seemingly reinforcing the other, but with a wholeness of commitment to each that made each its own full-fledged enterprise. The techniques of oil painting, and of watercolor, gouache, pencil, charcoal, collage, were mastered early on but never completely taken for granted. Even more, the diligent observation of nature and of the human form could somehow never be exhausted in his ongoing quest.

But the third incontrovertible attribute of Diebenkorn's art is its deep and complex yearning for idyllic human empathy and desire, an expression of luxe et volupte. He had an impulse to engage the traditions of such draughtsmen as Courbet and Gericault, at least in the sense of their command of human psychology. This painter is most commonly compared with such peers as Willem deKooning and Mark Rothko; he, like them, worked through an apprenticeship leading to a kind of consummate abstraction. It is time to consider that these more fully commited abstractionists never remotely attempted, much less achieved, Diebenkorn's command of a language of psychological, even narrative, sensuality. This vocabulary sprang from the same kind of synthesis of traditional craftsman discipline, and searching experimentation, that we associate equally with Matisse and Picasso. Both of them obsessively studied nature. Both studied and dissected and offered up their tributes to the female form, in its infinite manifestations.

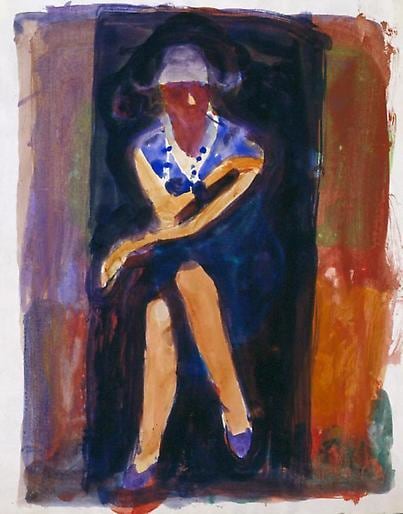

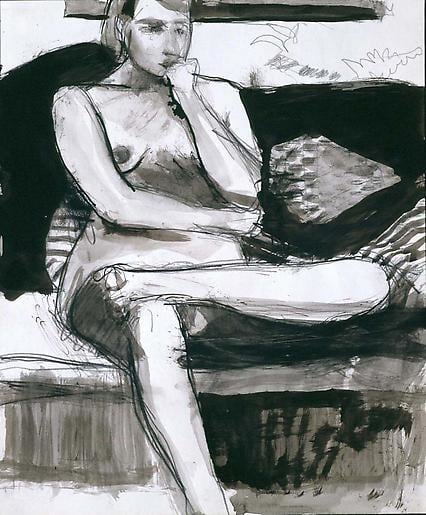

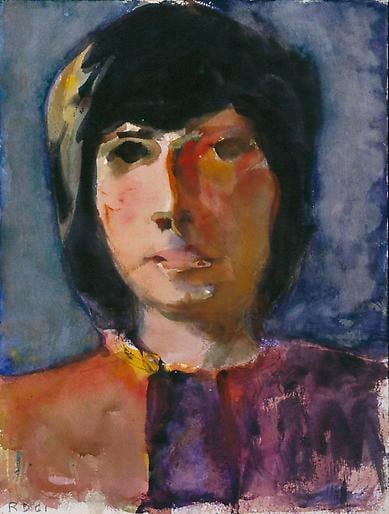

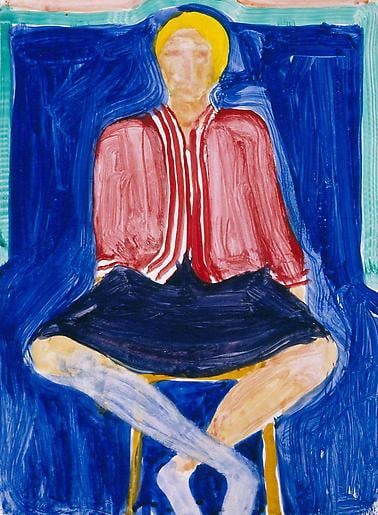

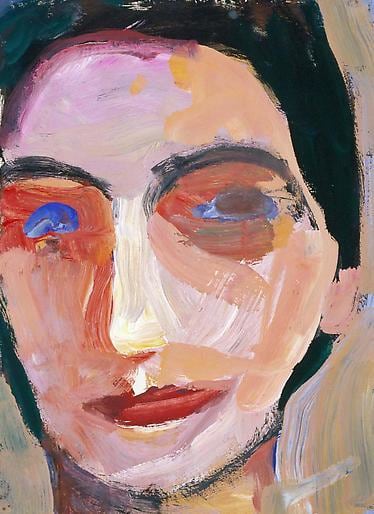

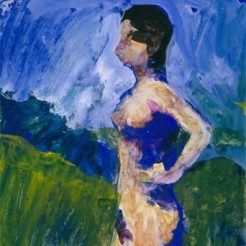

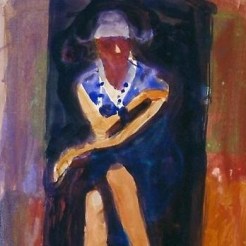

During the years from about 1955 to 1967, Diebenkorn organized frequent studio sessions with models—sometimes with fellow artists, other times alone. His searching, inventive attacks on the ancient problem of capturing (or posing) the figure, and the figure's relationship to architecture and furniture and draperies, suggest a discipline worthy of Ingres or Degas. Yet even more intense was Diebenkorn's habitual scrutiny on a less deliberative level, of facial expression and of subtle relationships among textures, colors and light-and-shadow compositions that occurred constantly and without artifice or conscious arrangement. Richard Diebenkorn, that creator of the famously grand, opulent and luminous Ocean Park paintings, turns out to be one of the twentieth century's most accomplished masters of modernist figuration, and of the intimate world of still life and of ordinary domestic existence. Faces, however, presented an artistic problem that would come into opposition with his endless search with an overall rightness, or fullness, created within a single drawing or painting. Anyone who has mastered the handling of the human figure at the level achieved by this artist will have spent countless hours drawing from life, and will have made endless sketches. Diebenkorn was careful to distinguish between works made as studies, or works not completed, or not finally satisfactory to himself, that were consciously kept apart from the official oeuvre. But that others of such wholly integral quality as these haven't been circulated, constitutes an event of major significance. Objects such as 930, 928 and 868 are now being introduced into the Diebenkorn canon alongside many beloved images whose familiarity will make these new ones all the more ready for study and delectation. These works fall into several types: the charcoal drawings, the more elaborate charcoal and ink wash drawings, and the more "fleshed out" gouaches. Within these groups are other categories—reclining or seated figures, standing figures, and heads. Diebenkorn's subjective separation of these genres, or artistic sub-traditions, itself gives us clues to his habitual engaging of the art of his forbears. For as restlessly independent and experimental an artist as he was, he grounded his achievement in French modernism, primarily that of Cezanne, Matisse and Bonnard. With this exhibition, we are also drawn to evince such an artist as Edvard Munch: who else recalls so immediately the compositional symmetry and the rhythmic, halo-like brushwork around a figure as the seated woman in #2088? Richard Diebenkorn was ultimately searching for a sort of verisimilitude of mood, or of deeper emotion. Attitude was everything—attitude of physiognomy or posture, of the feeling of the moment shared by viewer and subject. The miracle of these works resides in their repleteness of being—their existence in complete emotional pockets of being. Diebenkorn tended to privilege works by other artists on terms of their power to embody an honestly conveyed state of being—or even just a passing state of mind. It could be modest, but it had to be felt, and it had to be replete. Diebenkorn often experimented with a mode of working in opposition to the sinuous, free-form linearity he so deftly commanded in his charcoal studies from the model. This other idea led him to an absolutely focused symmetry, always in small scale. The impulse was sometimes realized in abstract form, but is most fully demonstrated in the small faces or heads made in various media, ranging from oil on panel to watercolor on paper. The problem of physiognomy in his work haunted him as it did virtually every modern artist from Manet to Matisse, but in Diebenkorn's case the challenge was quite particular. He struggled in the matter of the recognizable identity of a person when it was rendered in full figure, sometimes resorting to a sort of generalized facial treatment rather than giving in to the convention of the portrait. The positioning and gesturing of the body often conveys more about the person represented, or thought of, than does the facial expression. On the other hand, Diebenkorn's concentrated faces, or "heads," as he called them, zero in on their subjects (usually generic, occasionally specific) in the most naked way. There is a kind of brutal confrontation implied in some of the face paintings that contrasts decisively with the much more attenuated psychology of the full figures. And yet the intimations of German Expressionist imagery—Jawlensy in particular—are usually close to the surface. Consider such an image as No. 3604. In this exhibition, the several ravishing charcoal, ink and ink wash drawings may seem to dominate the field. This medium was one of Diebenkorn's most fully expressed genres. But it doesn't take long to grasp the equally original seduction of his color drawings. It is as if he could shift from one to another of these absolutely different genres, or styles, with impunity. Although we know that Diebenkorn was often attracted to experimenting with color, his palette was sometimes consciously tamed, in the sense of being non-Fauvist, or of bearing a clear relation to the psychologically observable world. When he broke out of this habit of creating seemingly naturalistic chromatic worlds, to allow color and composition to inhabit an arbitrary, highly aestheticized, realm, he could invent incomparable worlds. Two pictures illustrate this point—Nos. 2192 and #3602. It is impossible to imagine either of these images succeeding in any other palette than what is proclaimed. Color becomes the subject; line and texture bolster color; psychological undertones issue from these (abstract) attributes, rather than from the expressionism more common in this exhibition. A safer, if exquisitely rich, palette, characterizes a gouache and watercolor which, while modest in scale and "conventional" in genre, shows Diebenkorn at his most confident, and most replete. The image of a nude standing in profile, facing to her right, left arm akimbo, synthesizes figuration and landscape, color and spatial composition, tradition and innovation. The monumentality created by the erectness of the figure, legs sharply truncated, sculpturally commanding purple-blue shadows anchoring her corporeality, demonstrate the artist's ability to compete with his many classical forbears. This is not a typical Diebenkorn composition. And yet it is incontrovertibly his. The repertoire is extraordinary.

Jane Livingston

Copyright 2003