Berggruen Gallery is pleased to present a solo exhibition of works by Lucy Williams, on view May 18 – July 1, 2017. The gallery will host a reception for the artist on Thursday, May 18 from 5:00–8:00 p.m. Lucy Williams: Pools will showcase eight bas-relief collages of the mid-century modern pool in its various iterations, from private and residential to urban and municipal, as well as several examples from other bodies of Williams’s work.

Williams takes mid-century modern architecture as her subject matter, the clean lines and open spaces that dominated the built landscape of the 1920s to 1960s are immediately noticeable in each of her pieces. Working from photographs of real-life architectural spaces often taken at the time of construction, she creates collages of buildings designed by luminaries like Mies van der Rohe, Walter Gropius and Philip Johnson, as well as, if not more often, by lesser known and forgotten architects. In many cases, the real buildings that inspire Williams have been destroyed or drastically modified over the years, allowing Williams’s work to stand in as miniature substitutes for the lost originals.

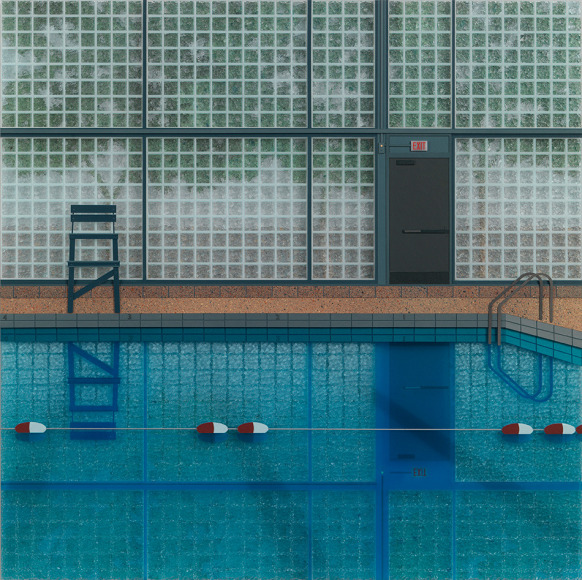

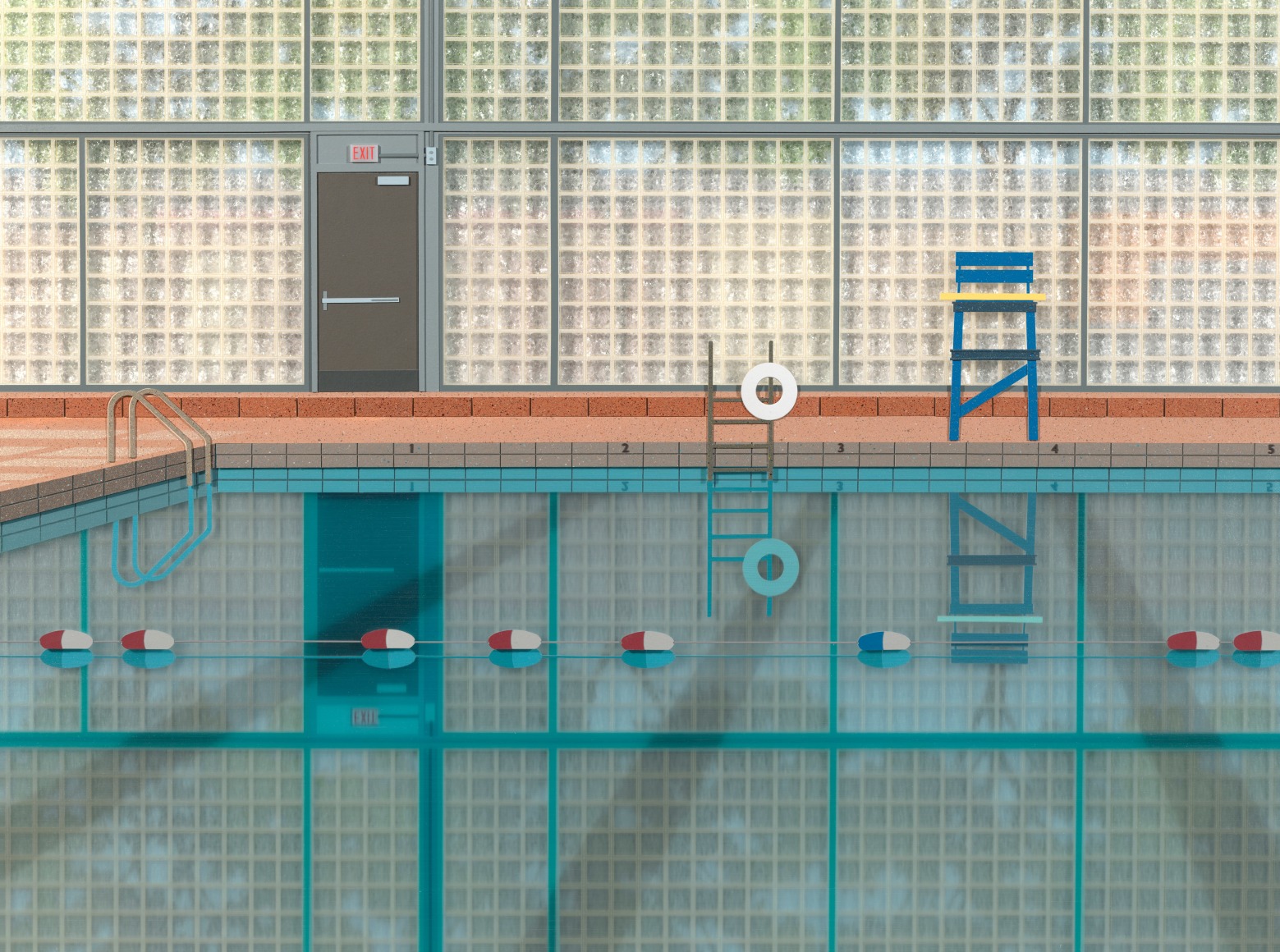

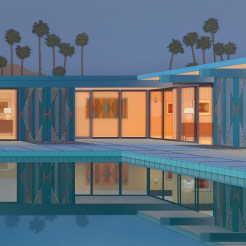

Williams, however, “is not simply making illusory doubles of her living subjects.”[1] She, in fact, adopts, explores and reinvents these buildings through her own unique form of three-dimensional collage, creating intricate and delicate bas-reliefs filled with their own unique character that lifts the architectural subject matter to another level of existence, and thus appreciation. Williams builds her works layer by layer from the interior of the building outward using a myriad of materials, such as paper, paint, board, Plexiglas, Jesmonite, filter gels, cork, balsa wood, wood veneers, piano wire, fabric and thread. These collages (if it is even fair to refer to them as such since they surpass what is commonly referred to as collage by leaps and bounds), are small in stature, rarely exceeding 35 inches in height and width and an inch and a half in depth. Every element is carefully cut and formed, placed and fitted together with infinite care and precision. These works are lovingly crafted, warm and inviting depictions of what is often mis-remembered as austere.

An important aspect of Williams’s reliefs is the fact that they are unpeopled. While initially the viewer may interpret this lack of figures as an expression of the artist’s feelings about the New Architecture and its impact on society, or as a commentary on the inefficacy of this building style to fulfill society’s needs, however when examined more carefully, the evidence of human inhabitation and occupation is rife throughout the artist’s work. Whether indicated by a door standing ajar in a municipal space (House Pool), the variation of window dressings from unit to unit in an apartment block (Great Arthur House), or from the disarray of books on a shelf (The Viennese Bookcase), or even a tea kettle on the stovetop as if just placed there and set to boil (Palm Springs), the human presence is undeniable. These spaces are clearly used and enjoyed by people.

In her pool series, which encompasses depictions of both private and public pools, Williams takes her explorations of mid-century modern architecture to another level. In these works, arguably more than in any other body of her work, she plays with perception and our conceptions of space and reality by introducing the element of water, which allows for transparency, reflection and distortion of the built architectural forms. In Palm Springs, the reflection is mostly straight forward, mirroring the architecture of Craig Ellwood’s open plan residential design. The forms and colors of the structure and its surroundings, flipped upside down, muted and constrained to the rectangular shape of the pool deck, are imbedded in layers of Plexiglas. This depiction illustrates the beauty and potential of water to highlight and heighten the impact of the architecture. In other examples, such as Community Pool, the precision of the reflections is so convincing that viewers may question whether they are actually seeing reflections after all or an extension of the room itself, not to mention the viewers’ momentary suspension of disbelief that they are looking at a real reflection rather than a fabricated one. The longer you look into Williams’s pools, the more you are mesmerized and lulled into the work and made to be a participant in the scene. Laura McLean-Ferris describes this phenomenon, “The cool precision of the swimming pool architecture, reflected in the water, creates an unnerving sense of perspective, in which the eye wanders, as though entering the water, only to trip over on indicators of flatness rather than depth. We find ourselves caught in the push and pull of a seductive non-zone.”[2] The magic of these pieces, aside from the beauty of their execution, exists in this non-zone, this nebulous space where reality and vision are uncertain and the uncertainty is hypnotic and pleasing. When realization hits, whether from seeing the thread of the lane lines or the glare off the Plexiglas, the viewer is even more stunned to remember that not only is this vision not reality, but that this non-zone is created from mere papers and plastics and wires.

Williams’s municipal pools also communicate a powerful message of human harmony. The actual purpose of these community pools in society was to provide a site for recreation and congregation. In Williams’s portrayals of these spaces, she creates an idyllic location for people to live out their lives. For the architects of the day, these spaces were in fact meant to not simply function as showpieces but to serve the communities. The utilization of standardized and rationalized architecture, as pioneered by Gropius, was not simply to fulfill aesthetic concerns, but to raise “the social level of the population as a whole.”[3] In the utilization of technological advances in engineering and materials, buildings could be constructed in components, thus increasing efficiency. Williams, in so eloquently describing the architecture and its potential, not only creates a stand-in for the original, she allows the architecture to live up to its potential, to be its truest self and accomplish the socialist agenda of New Architecture and the Bauhaus. Her work animates and humanizes the architecture of the day and allows the purpose to be attainable, for the open, light and transparent space attained through new discoveries with steel and concrete to provide communal spaces in the form of centers for education, congregation and recreation.

In addition to her pools, several pieces from different bodies of Williams’s work will be exhibited to provide an opportunity to see a crosssection of Williams’s artistic output. It is in these works that Williams’ concern with the utopian ideals of New Architecture come to life. The hope of architects such as Walter Gropius was that through standardization and rationalization, architecture was “raising the social level of the population as a whole.” Williams’s undeniable desire to attain these ideals by capturing a slice of time (whether real or potential) in her architectural collages, is fully flushed out when you see her work as a whole. In Bousefield School, for example, Willaims depicts the modular façade of Chamberlin, Powell and Bon’s primary school built in 1956 in North London, which was designed with large panes of colored glass to teach children about the theory of color mixing. This work, in the intricate details of the interiors filled with books and plants and appliances, acts as the stage in which the architecture is allowed to play out its role of elevating society to a higher order.

Lucy Williams was born in Oxford, England in 1972. She received a BA at Glasgow School of Art in 1995 and a Postgraduate Diploma in Fine Art from Royal Academy Schools in 2003. Recent solo exhibitions include Festival, McKee Gallery, New York; and Pavilion, Timothy Taylor Gallery, London. Williams lives and works in London.

Lucy Williams: Pools, May 18 – July 1, 2017. On view at 10 Hawthorne Street, San Francisco, CA 94105. Images and preview are available upon request. For all inquiries, please contact the gallery by phone (415) 781-4629 or by email info@berggruen.com.