The Abstract Bischoff

by Bill Berkson

For most historians and critics, the Elmer Bischoff story begins and ends with his prominence for twenty-some years as one of the Big Three (David Park and Richard Diebenkorn were the others) among Bay Area Figuratives. But Bischoff's schooling and the works of his earliest maturity were in abstraction and he likewise spent the last fifteen years of his life painting abstractly in a manner radically different from that of his youth.

Commenting in Artnews on Bischoff's first New York show, at the Staempfli Gallery in 1960, Fairfield Porter began by calling him "the most magnificent performer of all the Californians seen in this city who have given up abstraction in favor of realism." Accordingly, Bischoff's contributions to the initial surge of abstract expressionism during the 1940s and early '50s have been largely ignored, and, despite the admiration of other, mostly younger painters, the audacities of his late work tend to be looked at askance. Born in 1916, Bischoff belonged to the generation of painters who made abstraction the dominant mid-twentieth-century genre.

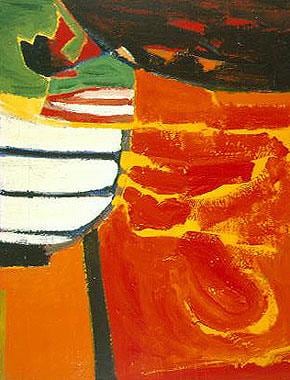

His most telling pictures, whether figurative or abstract, succeed by dint of his passion for color. They are full of tensions between an epicure's delight in the material, protean facts of painting and his oft-stated ambition to create pictures that would sweep all such facts aside, to arrive at what Bischoff himself called "totality," a wholly encompassing vision capable of striking chords deep in the viewer's consciousness. Anything less was too limiting. Students who took his classes the University of California, Berkeley, recall Bischoff as "a twinkling Buddha" extolling the virtues of "vague" as opposed to a too-clear partiality of image: above the attainable, "stamped-out" product, he favored the more arduous, open-ended personal search.

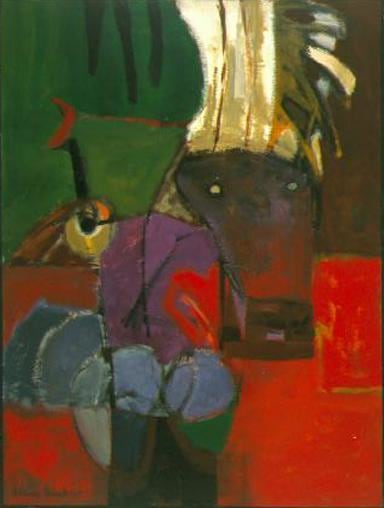

Many of Bischoff's early abstractions might just as well be seen as very limber variants of still life or landscape, exfoliate in paint. The important thing was to cover the canvas surface with more surface and to make that overlying surface sing. His virtuoso figure paintings harbor non-descriptive areas where, as John Ashbery said of Bonnard's pictures, "shapes dissolve and outlines swoon." As with David Park's Golden-Age-ish nudes, Bischoff's way of piling on raw effect by the primeval brush load signals a romantic yearning to get beyond what he called "the customary self," to let each picture supply its own discrete Arcadia. It's as if only in such circumstances could the kind of sublimation occur that would cast a direct line from visual fiction to inner life. Bischoff's abstract works have little of the troubled look of portentousness of his figure paintings. The earliest ones date from when Bischoff, aged 30 and just out of the Air Force, came under the spell first of Mark Rothko (in the latter's "mythopoeic" period) and subsequently (though less bindingly) of Clyfford Still. For all their ingenious cropping and sportive graphic devices, these paintings feel less like full-fleged performances than workouts in a generalized idiom – the local "open-form" manner soon to devolve listlessly toward what Lawerence Ferlinghettin in 1955 would call "the final Asia of the Abstract."

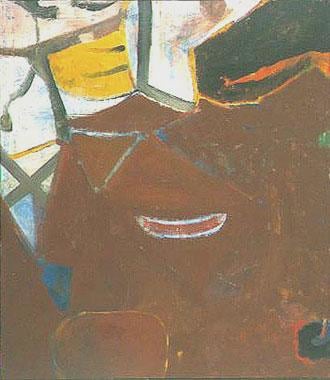

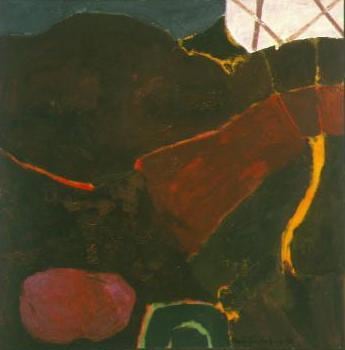

The 'twirling, strutting and flying forms" that Alfred Frankenstein observed in 1946 can be spotted in many of the artist's late paintings, but with considerably more elbow room to make their motions felt. The more distinctive pictures dating from a couple of years later are lyric fragments, intimate and dinward leaning, with staked-out, taut patches of cloisonne color. Their colors tend to glower or blush. Hypersensitive tangencies and unruly tilts push the scale of each picture up and out, and the ones with the greatest scale put all hesitancy aside and kick into a soft-shoe kind of humor. The tautness Bischoff sustained well into the 1950s required some slackening; you can see how, eventually, figuration freed up Bischoff's color as well as his feelings for masses within the physical expanse of the surface until around 1970 when the energy of that intermediate pursuit ran out and Bischoff declared it "too much of a one-way street."

Bischoff literally went out in a blaze. The shaggy symmetries and incantatory brilliance that are the glories of the late pictures are suggestive of some cosmic instigator feverishly shooting the works. (In the '70, Bischoff, ever fascinated by esoterica, had been reading up on Gnostic creation myths.) Here paint is more choreographed than put; incandescence – reticulated, comparable in its deviousness to the "unpredictable light" Bischoff admired in El Greco – rules. There are quadrilateral pockets that echo with tick-tock nonchalance the ninety-degree angles at the corners. Played against the steady no-dynamics of the square or near-square formats Bischoff favored throughtout his career, what the painter and Bischoff's one-time Berkeley colleague Christopher Brown calls "the look of noise" is panoramic and extrovert. The coalesced glyphs parade or tumble across celebratory surfaces – acrylic ribbons, slashes, scrapes and scrubbings; rubato hatchings, darts, cartoonist force lines, charcoal and chalk addenda and silhouettes with odd, jagged contours that may have been tracings of objects held against the canvas (a partial list, only, of the many incidental marks involved). Convulsive in the sometimes audible cackling of a plain-painter-gone-visionary exultation, they all fit.